In the early 1950s, Kauko Kahila began correspondence with F.A. Reynolds Co. on more effective ways of extending and playing the low-register range of the bass trombone. With a standard one-valve change to F, the lowest playable chromatic is the low C, leaving a half-step gap to the pedal B♭ — bass trombonists typically had to either "lip down" the C to approximate the B or pull tuning slides out, extending the instrument's length to get close to the desired B, but leaving the horn ill-tuned for other notes until the slides could be readjusted.

Like other manufacturers at the time, Reynolds had accommodated the latter approach by providing an F attachment with an extra-long tuning slide to E on their original Contempora "Symphony" model (1949). However, Kahila (and many others) wanted to more accurately and more easily play passages such as the low B glissando in Bartok’s “Concerto for Orchestra” (written in 1944 and premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, it was a standard piece in the orchestra's repertoire and a recurring challenge for Kahila, having joined Boston in 1952).

In 1955-56, Reynolds introduced a new Contempora bass trombone, the “Philharmonic” model, with a modified F attachment that had two tuning slides: the main F tuning slide for conventional use and a second slide that could pulled to achieve E tuning, then pushed in to return to F. This was an advantage over the conventional “Symphony” model with its single tuning slide, but still required a player to manually adjust a tuning slide while playing.

The "Philharmonic" model proved to be popular with orchestral bass trombonists. Kahila had joined the BSO playing the Schmidt bass trombone originally owned and played by his teacher, Lillebach; he switched to the "Philharmonic" bass trombone as a lighter and more responsive alternative for Boston Pops concerts. Even after the double-valve Reynolds model was available, Kahila preferred to play the single-valve Reynolds or Schmidt as his "regular" horn.

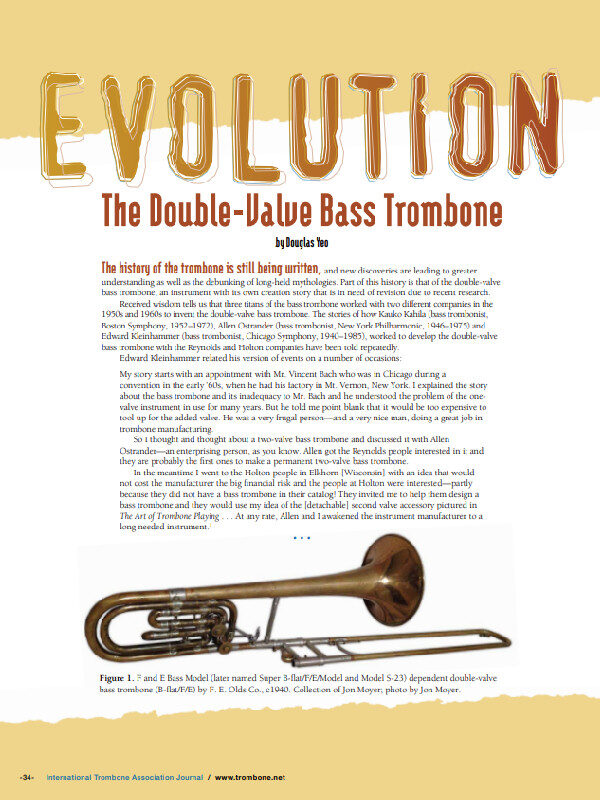

Kahila, Allen Ostrander (New York Philharmonic Orchestra) and Louis Counihan (Metropolitan Opera Orchestra) all endorsed the model. Counihan appears in 1956 print ads praising the new model and all three are featured in late 1950s Reynolds catalogs. According to records in the NYPO digital archives, Ostrander switched from a Conn 70H to the "Philharmonic" model in early 1957, taking it on the orchestra's spring tour that April. His instrument is recorded as serial number 45190, which matches an early 1957 date, and is valued at $395, the same list price in the 1958 catalog.

Kauko Kahila

Bass Trombone, Boston Symphony Orchestra

Allen Ostrander

Bass Trombone, New York Philharmonic Orchestra

Louis Counihan

Bass Trombone, Metropolitan Opera Orchestra

Not fully satisfied with the solution provided by the "Philharmonic", Kahila continued to experiment with designs that would engage the E tubing only when needed through the press of a trigger and a second rotary valve. He claimed that he came up with the design for the double-valve tubing by laying out strands of string on the floor — this might suggest the origin of the unique “Reynolds wrap” design that extends the F-attachment tubing forward toward the bell in what Doug Yeo calls "a radical change ... and an early example of what we now call 'open wrap'". Kahila sent the designs to Reynolds and they agreed to move forward with a pilot. In an interview with Douglas Yeo, Kahila described his role in the development of the double-valve bass trombone:

The double valve came about when we were playing the Bartok Concerto for Orchestra which, as you know, was commissioned by Koussevitsky and premiered by the Boston Symphony. I figured there must be a way to get the low B, and if I added another length of tubing I could do it. I made the plans for it and submitted it to the Reynolds Company and they said, "Sure, we'll do it." So it worked. But you know the mechanics of the trombone; the air doesn't go as freely through the valves. But I didn't have too much trouble. I used to make the gliss pretty well with it. The secret is to hit it, and when you move the slide, you're already off the second valve. Anyway, Reynolds gave me one of the horns since I had the idea and then they commercially marketed it.

In another interview, Kahila noted that there was no discussion of royalty payments with Reynolds and that he was just happy to have a trombone where he didn't have to "fake [the low B] anymore." [Cape Cod Times. May 20, 2002. Pages B1-B2.]

As a result of the discussions with Kahila, Reynolds built three prototypes in late 1957 and brought in Ostrander and Counihan for testing and feedback. The three musicians met over the winter of 1957-58 to discuss the prototypes—they requested changes to the placement of braces around the valve section and suggested the use of saxophone-style key rollers to aid the dependent dual-trigger design. Reynolds began work on implementing their recommendations and that fall, after playing the prototype on a summer tour throughout Latin America, Ostrander sent his model back to the factory to be upgraded. Ostrander's instrument was serial number 49479 and valued at $500 (list price in 1958)—unlike Kahila and Counihan's prototypes with the standard Reynolds bronze bell, Ostrander had requested a yellow brass bell.

Commercially introduced in the fall of 1958, the “Stereophonic” Contempora was the first of a new generation of widely available double-valve bass trombones, along with the Bach 50B2 (1961), the Holton TR-180 (1964) and the Conn 73H (1968).

Editor's Note: Contrary to what has been previously claimed on this site—and by many other sources—adding a permanent second valve to the Reynolds bass trombone was not a new or completely original solution. Former Boston Symphony Orchestra bass trombonist Doug Yeo explored the range of historical approaches and solutions to extending the range of the B♭ bass trombone in his 2015 article, "Evolution: The Double-Valve Bass Trombone" for the International Trombone Association Journal, debunking some of the long-held mythology around the Contempora and other popular models.

To grossly summarize, F.E. Olds produced the first B♭ bass trombone with two valves permanently attached in 1938, but it was undersized and never caught on in the professional symphonic world outside of the Los Angeles studios. In 1952, Edward Kleinhammer (Chicago Symphony) had an instrument repairman convert an unspecified bass trombone (Conn 70H?) into a double-valve bass and later worked with Holton on the TR-180. Lawrence Weinman (Minneapolis Symphony) convinced Vincent Bach to make the first prototype of the Bach 50B2 in 1956, using the Olds bass as a reference point. And Kahila, with Ostrander and Counihan, worked with Reynolds in 1957-58 to bring the Contempora double-valve bass to market. While neither first or wholly original, the "Stereophonic" firmly stands in this historical stream of experimentation and innovation.

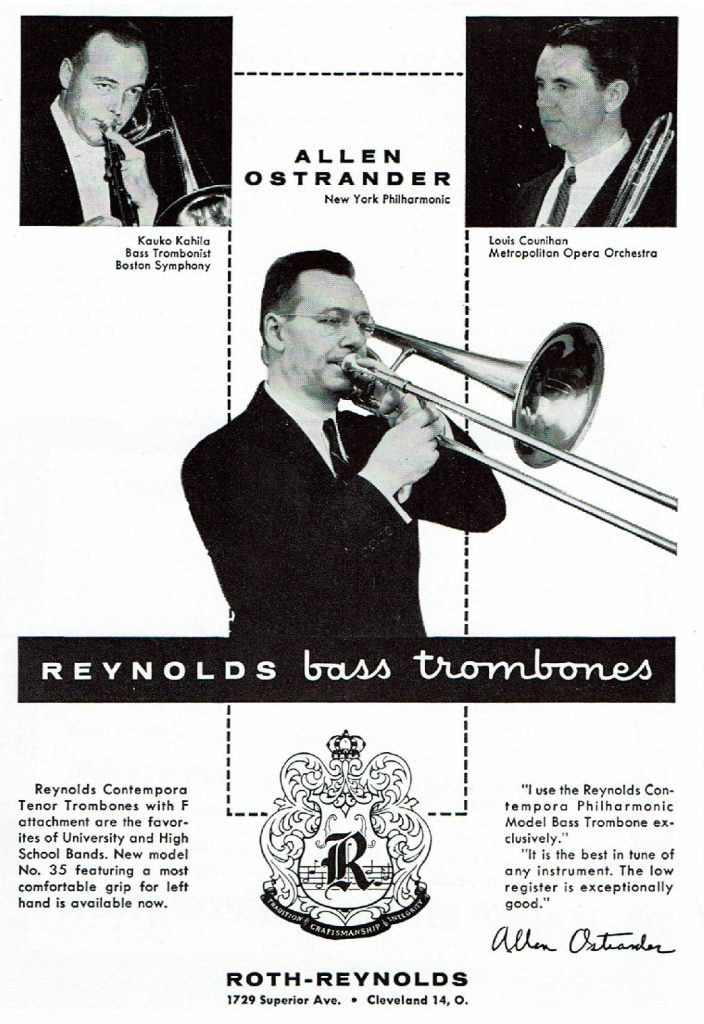

Whereas Kahila ultimately preferred the single-valve "Philharmonic" bass trombone for daily playing, Allen Ostrander quickly championed the advantages of the “Stereophonic” double-valve design for his NYPO playing and teaching methods. An image of the Reynolds double-valve section appears on the front of my copy of Ostrander’s “Double-Valve Bass Trombone Low Tone Studies” method book. Ostrander also appears to have been somewhat of a gearhead, ordering a second Reynolds horn and mixing and matching bells and valve sections from different manufacturers to see how they played. Reportedly, he attached an old Conn 9½" yellow brass bell and .547/.562" dual-bore slide for the majority of his NYPO playing.

The "Stereophonic" originally featured attachments that provided F and flat E tuning as this was the simplest way to add the chromatic low C and B notes to the end of the slide. As more double-valve models entered the marketplace in the 1960s, players began to express a preference for F and D attachments, as the latter made it more efficient to play in the low register by placing the B closer in on the slide. Finally, in response to the increasing number of customer requests, Zig Kanstul, the factory superintendent in charge of Engineering and Design at Olds' Fullerton plant (where Reynolds instruments were then made), designed an extension that fit into the existing E attachment tuning slides, lowering the double-valve pitch to D.

A factory-made D extension for the "Stereophonic" Contempora is shown below in the upper left, along with several examples of custom-made extensions that have been spotted "in the wild".

Another customization that some players have made is splitting the dependent trigger paddles so that different fingers operate each one—usually this done for specific ergonomic reasons or if a player is more comfortable with a trigger layout from another instrument.

Kauko Kahila

Kauko [pronounced cow-ko] Emil Kahila was a first-generation American, born just outside of Boston, Massachusetts, in 1920. His parents immigrated from Finland around the turn of the twentieth century. Kahila's father and grandfather were active community band musicians in the New World and he started playing alto horn, then trombone, at a young age.

Kahila studied trombone from age 16 at the New England Conservatory under Hans Durck Waldemar Lillebach of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1934-1941). Kahila's book of trombone etudes was written while he was a student at NEC; dissatified with the available published studies, he wrote one etude a week for a semester and brought them in to play for Lillebach. They were eventually published by Robert King.

Kahila had the opportunity to audition for Lillebach’s chair in Boston when the elder musician left for Cleveland in 1941, but passed out of respect to his teacher and not wanting to be the "young buck" to take his chair. John Coffey filled the position instead and played through the 1951-52 season before leaving to focus on his music store business.

After graduating from NEC, Kahila joined the Houston Symphony Orchestra where he played bass trombone from 1941 to 1944, including service time spent in the Army Air Force Band during the 1942/43 season. In 1944, Kahila secured the bass trombone position with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. He played in St. Louis for eight seasons before joining the Boston Symphony Orchestra near the end of the 1951/52 season.

Kahila retired early from the BSO in 1972 to take care of family. He died in 2013 at age 93 in his home. The following photos of Kahila were provided courtesy of Douglas Yeo. Please do not copy or redistribute without permission.

Allen Ostrander

Note: The following biographical text is used with permission from the Ithaca College Trombone Troupe.

Allen E. Ostrander was born in Lynn, Massachusetts on December 14, 1909. He began trombone study in 1923 with Aaron Harris and graduated from the Ithaca Conservatory of Music in 1932 with a B.S in Instrumental Music where he studied trombone with Patrick Conway and Ernest Williams. Later study with Simone Mantia, Gardell Simmons, and Walter Lillebeck also contributed to his remarkable professional playing career.

Following graduation, he attended the National Orchestral Association in New York City for three years before landing his first professional position as bass trombonist with the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C. Following one season with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in 1937, he was selected by Arturo Toscanini as bass trombonist with the NBC Symphony, a position he held until 1946. Between the years 1942 and 1945 he spent three years in the U.S. Army before returning to NBC for a final year. From 1946 until his retirement in 1975 he served as bass trombonist with the New York Philharmonic.

In addition to his outstanding playing career, Ostrander has taught on the faculties of West Virginia Wesleyan, Julliard, the Hartt School of Music, Columbia Teacher's College, and Ithaca College. He also co-designed the Reynolds Contempora double-valve bass trombone and has authored a number of method books for this modern instrument. In addition to his original compositions for bass trombone, he has arranged, transcribed, and edited numerous other brass works, of which over one hundred are still in print.

Since retiring to his current home in Ithaca, New York in 1975, he has been honored by the International Trombone Association for his lifetime achievements and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Music from Ithaca College in 1993." [Ed. Mr. Ostrander died in 1994.]

Photo credits: NYPO images reproduced from The Trombone Forum. All other images courtesy of ElShaddai Edwards.

The purpose of this website is to preserve the history of the F. A. Reynolds Company and the distinctive qualities of its brass instruments. Contempora Corner and contemporacorner.com are not related or associated in any way to the former or current F.A. Reynolds Company.

Copyright © 2004-2025 ElShaddai Edwards. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use.

5 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

I have one of these Contempras: Single valve with E pull. Comments on this site about intonation are absolutely correct. I also have a King 4B Silver Sonic. The Contempra is far, far easier to play in tune. Period. It is almost like the pitches find me. I don’t have to find them. I use the Contempra for playing bass trombone and also 1st trombone parts. It works great!

I realized this after many A/B comparisons. This is an absolutely great horn. Very much under rated and under appreciated!

I owned a “Stereophonic” Reynolds bass a few years ago that had been modified by Dan Oberloh in Seattle, WA. It had a “D” slide patterned after a King “Duo Gravis” and had a split trigger. The workmanship was excellent. I traded it for a mint Conn 88H. I’d post pictures but see no way to do so. You did a fine job on overhauling the website !

I don’t know if this will help, but Scott Sweeney in Raleigh, NC fabricated a D crook for my Yamaha 612. Did a beautiful job, He plays bass trombone, so he really knows his stuff.

https://www.sweeneybrass.com/

Thank you for the tip. I do appreciate. George

I was wondering if anyone still manufactures the “D” extension for my Contempera “Stereophonic: bass bone. I wish to purchase a “D” extension for my horn.

Thank You,

George Paree